US estate tax strategies for noncitizens and nonresidents with US assets

If you have US-based assets, here are some key things to know about the United States estate tax for foreign nationals.

Last updated January 16, 2026

High net worth individuals worldwide look to the US to provide a relatively stable and safe haven for their family wealth. However, when the time comes to transfer that wealth to the next generation, there can be unforeseen tax consequences. Foreign nationals with US assets may be subject to US estate taxes, regardless of their residency or citizenship status, even if they live permanently abroad. So, careful planning is needed to minimize potential tax losses. Here’s an overview of things to consider, but keep in mind that estate planning for high-wealth multinationals is an inherently complex topic, and you should be prepared to seek appropriate legal and accounting advice for your specific situation, and the jurisdictions in which you have assets.

High net worth individuals worldwide look to the US to provide a relatively stable and safe haven for their family wealth. However, when the time comes to transfer that wealth to the next generation, foreign nationals with US assets may be subject to US estate taxes, even if they live permanently abroad. So, careful planning is needed to minimize potential tax losses, and recent changes enacted in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act should be taken in to account. Here’s an overview of things to consider, but keep in mind that estate planning for high-wealth multinationals is an inherently complex topic, and you should be prepared to seek appropriate legal and accounting advice for your specific situation, and the jurisdictions where you have assets.

Get help from a team that understands the challenges faced by foreign nationals.

The Guardian Global Citizens Program provides concierge life insurance services for foreign nationals with significant financial and family ties in the U.S. and other countries, tailored to your unique situation, residency, and immigration status.

Residency status and the US estate tax disparity

The United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) defines estate tax as a tax on the transfer of tangible and intangible assets located in the United States. Tangible assets often refer to real estate located in the United States. Intangible assets can mean stocks held in a US corporation, personal bank accounts, insurance, trusts, and annuities. Estate and gift taxes are often lumped together because they share many of the same rules, rates, and exemption amounts. For example, US estate taxes are paid by the estate, not the person inheriting assets; similarly, gift taxes are paid by the person giving the gift, not the person receiving it. The tax rate for both is up to 40%. Most importantly, there is a combined exemption for lifetime gifts and estate assets, which, for most US taxpayers will be set at $15,000,000 per person for 2026 (up from $13.99 million in 2025). For married couples, this exemption is $30,000,000 1 However, not everyone will get the generous $15,000,000 exemption because eligibility is determined by residency status:2

Generally speaking, a US citizen or foreign national domiciled in the United States gets a $15 million exemption (starting January 1st, 2026); after that amount, their estate is responsible for paying up to 40% in federal estate taxes.

Non-domiciled foreign nationals get just a $60,000 exemption for estate assets, plus a $19,000 annual exemption for gifts ($194,000 for gifts to non-citizen spouses)2,3 — and are responsible for up to 40% of estate taxes above that amount. However, for non-domiciled individuals, the gross estate only includes only US-situated assets; the taxable estate (i.e., the part subject to estate taxes) is the portion of the gross estate that exceeds the exemption amount.

The estate tax exemption is not always well understood by residents and nonresidents alike; but because the exemption disparity is so wide, the tax implications for non-domiciled foreign nationals tend to be much more significant. However, with proper planning, there are ways that it can be addressed.

The estate tax disparity for US residents and non-residents

Status | Exemption | Estate Tax Rate | Applies To |

|---|---|---|---|

U.S. Citizen or Domiciled | $15M (2026) | Up to 40% | Worldwide assets |

Non-Domiciled Nonresident | $60K | Up to 40% | U.S.-situated assets |

Source: Estate tax for nonresidents not citizens of the United States, Internal Revenue Service, May 22, 2025

Determining domicile status

The first step to addressing US estate tax disparity is knowing which rules apply to your situation. However, it is not always easy to do. The US Internal Revenue Service domiciliary rules for estate tax purposes can be nuanced and complicated.2,3 For example, individuals present in the US on a nonresident visa (such as a G-4 visa) may be considered US-domiciled for estate and gift tax purposes, even though they are considered nonresidents for US income tax purposes.

Factors that determine your domicile status for US taxes

Length of stay in the US

Visa or residency type

Property ownership

Location of family and business interests

Why domicile matters for estate tax planning

Your domicile — the US tax authorities’ determination of where you live — helps determine more than just the size of your estate tax exemption. It also helps determine which of your assets are taxable in the US, and whether you are eligible for favorable treatment under a tax treaty. However, domiciliary rules are complex and often seemingly contradictory, so a qualified tax attorney is recommended to help navigate the process. Expert tax planning can also help nonresidents understand different ways estate tax liabilities can be increased or lessened depending on a person’s nationality and where their assets are located in the US:

Estate tax treaties with foreign countries: The United States has estate tax treaties with some foreign countries, which allow nonresidents more generous exemptions that can provide significant reductions to US estate tax obligations. Those countries currently include:4

Australia

Finland

Ireland

Austria

France

Italy

South Africa

Canada

Germany

Japan

Switzerland

Denmark

Greece

The Netherlands

United Kingdom

It’s important to note that these treaties may include both estate and gift taxes, and the specific rules and benefits depend on the applicable tax treaty.

US state estate and inheritance taxes: Certain US states impose their own estate and inheritance taxes in addition to federal estate taxes. Details vary by state and can be quite involved. Speaking with a qualified professional can mitigate risk and maximize advantages.

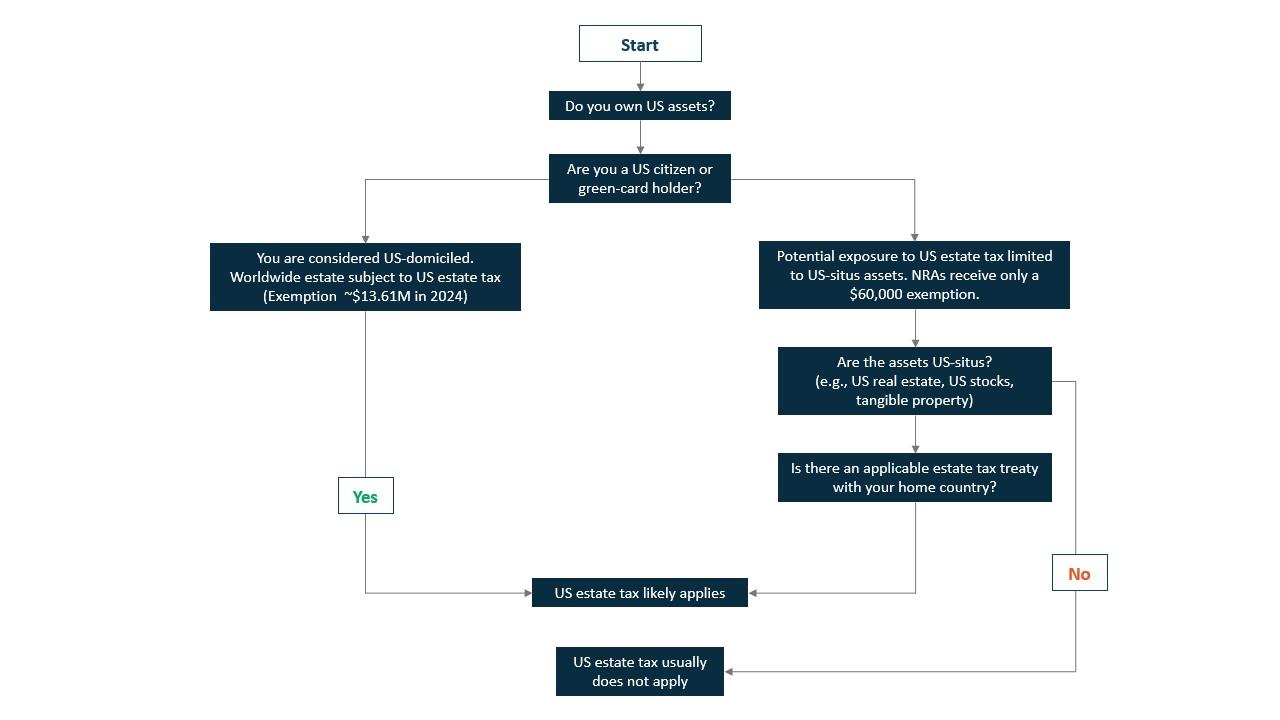

Is my estate subject to US tax?

Traditional hedge tactics against estate tax liabilities may no longer be effective

In years past, nonresidents could opt to transfer ownership of US real estate assets to a non-US holding company to eliminate estate tax obligations. Those legacy avoidance strategies now trigger new compliance risks under modern IRS rules and US tax laws, including:

FIRPTA: The Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act applies to nonresident foreign nationals, foreign corporations, LLCs, and partnerships, and imposes US income tax on foreign nationals who sell US real estate.

US Corporate Anti-Inversion Rules: These rules were designed to curb strategies once used by nonresident foreign nationals and multinational companies to reduce U.S. tax exposure by creating a “blocker” structure (an asset-holding US corporation owned by a foreign parent) that shielded those assets from U.S. estate and gift tax.

New rules target tax-avoidance strategies

Strategy | Old Rule | Current Law Impact |

|---|---|---|

Non-U.S. holding company | Avoided U.S. estate tax | No longer effective due to FIRPTA |

U.S. corporation “blocker” | Deferred liability | Restricted by anti-inversion rules |

Effective estate planning solutions for foreign nationals

Anyone who wants to protect the wealth they’ve accumulated should plan carefully for the best way to transfer assets to the next generation. However, nonresidents with US assets must be cognizant of a much wider range of laws and estate taxation rules across different countries. Estate planning strategies are especially important for nonresidents, as they can help navigate complex US estate and gift tax laws and maximize tax benefits, even for assets that don’t experience capital gains. The appropriate solution for your individual situation will likely be found in consultation with a specialized professional who understands your financial goals and is conversant with the rules in the jurisdictions where you live, have assets, and have relatives you want to leave them to. Having said that, there are two effective strategies you should know about.

Gifting assets

Giving gifts of cash, tangible personal property, or real estate interests to heirs while you are alive can be an effective way to transfer assets and, sometimes, help reduce estate tax obligations.

There is an annual exclusion for “present value” gifts of up to $19,000 for 2025,3 which means each individual can give anyone up to $19,000 ($38,000 for married couples) without issue, and you don’t even have to report it on your taxes.

When gifts go over that amount, you have to file a gift tax return for every person who receives more than $19,000 per year; and a non-resident will owe gift taxes of up to 40% on any sum over that amount.

However, if you are a US citizen or resident (domiciled), you don't necessarily have to pay gift taxes, because there is a lifetime exemption of $15,000,000 for all gifts to all recipients.

Spouses and marital transfers

When both spouses are US citizens, there is typically an unlimited deduction for estate asset transfers from one spouse to another. However:

If one spouse is a non-citizen, they do not qualify for the unlimited marital deduction.

In such cases, a qualified domestic trust (QDOT) can be established to defer estate taxes for a surviving spouse

This can allow the noncitizen spouse to receive income via the trust without being subject to estate taxes.5

Using US life insurance to overcome the estate tax disparity

Nonresident life insurance can help bridge the estate tax disparity, because death benefit payments are generally exempt from federal estate taxes. While the nonresident exemption for estate assets is limited to $60,000, life insurance benefits are considered to be separate from the estate and not subject to the same limitations. In other words, life insurance proceeds are generally not subject to US estate tax, which can result in significant tax savings for nonresidents. That also means that that money is transferred to beneficiaries without going through the probate process, which can be time-consuming for a large estate. These features could make life insurance an attractive wealth preservation and transfer vehicle for many foreign nationals with US-based assets. Permanent universal or whole life insurance that builds cash value can also provide a number of other advantages when it comes to estate planning and preserving family wealth:

Covering potential estate taxes: Life insurance proceeds can preserve the estate’s value by providing the liquidity needed to cover taxes without having to sell all or a portion of the holdings.

Portfolio diversification and risk mitigation: Permanent whole life insurance builds US-denominated cash value at a guaranteed rate, acting as a hedge against fluctuating exchange rates, and other forms of geopolitical risk.*

Asset protection: Life insurance policies are generally protected from creditors and bankruptcy, providing an additional layer of asset protection.

If you’re a foreign national with US residency, a Guardian financial professional will work closely with you on a one-to-one basis, and then tailor an estate planning solution that precisely fits your needs. Or, if you’re a nonresident with ties to the US, ask about the Global Citizens Program.

The Global Citizens Program

Guardian provides specialized life insurance solutions and services designed to meet the unique demands of high-net-worth international clients. Our Global Citizens Program allows qualifying clients to tap into a dedicated team that specializes in the more complex financial protection needs of clients with multinational interests — and provides white-glove service with the backing of one of the world's largest mutual life insurance companies. The program offers access to different types of life insurance, including permanent life insurance policies with provisions designed specifically for international clients. Clients must be non-resident, non-US citizens who demonstrate financial connections, holdings and/or family ties in the US. A dedicated case concierge team is assigned to help each applicant, and specialized underwriters evaluate submissions. Other amenities include a complimentary US trust review, translation services, law firm referrals, and more. To learn more, contact a Guardian financial professional.

Yes. If they have US-based assets over a certain amount, the estates of foreign nationals may be subject to US estate taxes of up to 40% on the fair market value of the assets. However, there is an estate tax exemption of $15,000,000 for “domiciled” (i.e., US resident) noncitizens. But if they are “non-domiciled” (i.e., nonresidents), the exemption is just $60,000, and the estate must pay taxes of up to 40% on all assets above that amount.1 Finally, rules will differ if an estate tax treaty is in place with the foreign national’s country of residence.

When a foreign national with US assets passes away, the US estate tax rules apply to those assets, whether or not that person is a resident of the United States. However, assets held abroad may not be subject to US estate taxes if the person is not a US resident.

The US estate tax exemption is based on country of residence, not just citizenship status. The nonresident estate tax exemption for foreign nationals is just $60,000, but US citizens and noncitizen residents have a federal estate tax exemption of $15,000,000. Life insurance can help bridge this disparity for nonresidents because death benefit payments are generally exempt from federal estate taxes.

The nonresident estate tax exemption for foreign nationals for 2025 is $60,000. It was set at that level in 1976 and has not been indexed for inflation or changed since then.6

Generally speaking, life insurance proceeds for a policy issued in the United States are paid out free of taxes, regardless of the citizenship status of the insured or the beneficiary.

Generally speaking, there is no limit to the amount of money a non-US citizen can inherit in the US. However, if the deceased is a non-resident, assets in their estate over the $60,000 exemption limit are subject to estate taxes of up to 40%. These taxes are paid by the estate, not the person inheriting the money.

There is no federal inheritance tax in the US. However, a non-resident non-US citizen may owe inheritance taxes to local authorities based on their country of residence.

Green card holders are, by definition, permanent residents of the US. As such, they qualify for the same $15,000,000 lifetime estate and gift tax exemption available to US citizens.

* Some whole life policies do not have cash values in the first two years of the policy and don’t pay a dividend until the policy’s third year. Policy benefits are reduced by any outstanding loan or loan interest and/or withdrawals. Dividends, if any, are affected by policy loans and loan interest. Withdrawals above the cost basis may result in taxable ordinary income. If the policy lapses, or is surrendered, any outstanding loans considered gain in the policy may be subject to ordinary income taxes. If the policy is a Modified Endowment Contract (MEC), loans are treated like withdrawals, but as gain first, subject to ordinary income taxes. If the policy owner is under age 59½, any taxable withdrawal may also be subject to a 10% federal tax penalty.

1 The Estate and Gift Tax: An Overview, United States Congress, July 4, 2025.

2 Estate tax for nonresidents not citizens of the United States, Internal Revenue Service, May 22, 2025.

3 Gift tax for nonresidents not citizens of the United States, Internal Revenue Service, July 15, 2025.

4 United States Income Tax Treaties - A to Z, Internal Revenue Service, January 3, 2025.

5 Estate Planning When a Spouse is a Non-U.S. Citizen, Calamos Wealth Management, July 18, 2024

6 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estate_tax_in_the_United_States

This material is intended for general public use and is for educational use only. By providing this content, The Guardian Life Insurance Company of America and their affiliates and subsidiaries are not undertaking to provide advice or recommendations for any specific individual or situation, or to otherwise act in a fiduciary capacity. Please contact a financial representative for guidance and information that is specific to your individual situation.

Guardian, its subsidiaries, agents, and employees do not provide tax, legal, or accounting advice. Consult your tax, legal, or accounting professional regarding your individual situation.